An Open Letter About Why the Names Had to Go

Since the beginning of American history, we have been murdering Indigenous people. Since the beginning of American history, we have been masquerading ourselves as them, taking pride in the fact that our land has such savage people. Even before this country was founded, Americans dressed up as Natives to fight off our enemies, take the Boston Tea Party for example. The famous event in which we stood up to the British, a starting point for the Revolutionary War, we wore Native Mohawk “disguises’’ in order to set ourselves apart from the British, to seem tougher, to gut punch them, to taunt and joke because that’s how we viewed Natives: as a joke. Now, of course we say we don’t view them that way anymore, but don’t we? Is chanting fake battle cries or wearing mock headdresses or calling ourselves Native to fight our enemy on a field really any different? I am a student at Hall High School who has just taken a genocide studies class. Native American mascots damage Indigneous people by perpetuating racism, dehumanization, and genocidal stereotypes.

Since European colonists’ arrival, Indigenous people in America have been victim of one of the largest genocide throughout history. Christopher Columbus’ arrival came with the deaths of 8,000,000 people through intentional spread of disease, slaughter, and cultural destruction. These patterns continued through the 16th and 17th century. With the United States’ foundation, “manifest destiny,” the belief that American settlers were entitled to America, was long used to warrant the destruction of Native communities. Starting in the mid 1800s, the American government continued its cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples by forcing Native Americans to assimilate into white, Christian, American culture through boarding schools. The mantra “Kill the Indian, Save the man” was often used to justify the breaking apart of families. In these boarding schools, Native children would be taught Catholicism, capitalism, to be ashamed of their culture and heritage, and to adopt supplementary aspects and values of white American culture. The schools would teach them that their native cultures were savage, aggressive, and uncivilized. Then they would marry and share a traditional American home with a white person due to their self hatred and desire for whiteness, gradually diluting their indigenous blood until they were no longer a threat or inconvenience to the United States government. This broke ties between the community and the child, “breaking the linkage between reproduction and socialization of (the) children in the family or group of origin” (Historian Helen Fein’s 1988 definition of genocide). The desired result can be seen throughout South America, in which a huge portion of citizens have indigenous ancestry, yet a vast majority of them speak Spanish and practice Christianity, most without knowing their Indigenous languages or cultures. This process continued with the Indian Adoption Project of the 1950s, in which adoption of Native children was promoted by the government. Although it ended in 1978 with the Indian Child Welfare Act (an act attempting to keep Indigenous children together), though not heavily enforced, both the US adoption and foster care system still contribute to the displacement of Native children. Still, the United States has not recognized the genocide, meaning the last stage of the Ten Stages of Genocide (of Genocide Watch), denial, still continues today. Indigenous lives are still persecuted today, largely by the blind eye of the US government and popular media.

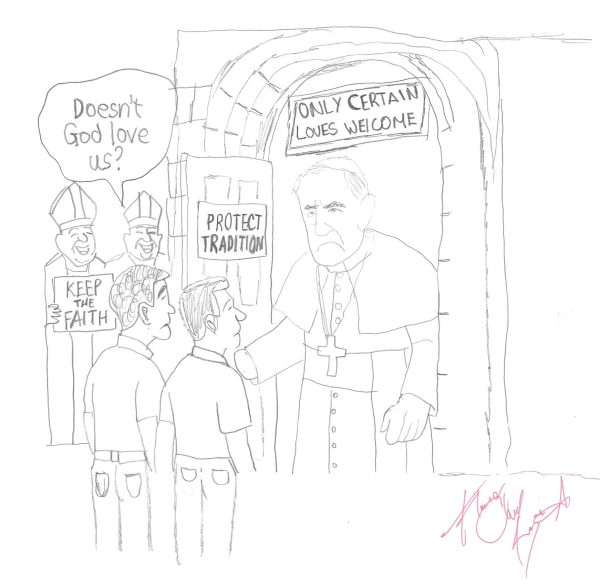

Dehumanization, the fourth stage of genocide, is the denial of a person or people’s full humaness or the removal of their humanity. Therefore, to counteract discrimination against Natives, we should not dehumanize people (revolutionary take, I know), including not boiling them down to a mascot. And yes, mascots can be people, but they are a caricatured version of such, meant to “bring good luck or…to symbolize a particular event or organization” (“Mascot Definition & Meaning”). Should we really be using an inaccurate, and, as called by many Natives, mocking, caricature of a people we committed genocide against to bring us good luck? Can said caricature really symbolize a school or team in which the population of Native people is just above 1 percent (Brenna and Castagna)? A 1997 documentary titled In Whose Honor? followed Native activist Charlene Teters’ protesting against the University of Illinois’ Native mascot Chief Ilinwek. This “chief” would perform at halftime making a mockery of sacred Native ceremonies. Teters described when her children saw Chief Ilinwek, who she tried to warn them about: Her daughter was trying to become invisible while her son was trying to laugh it off; they saw their traditions they respect being mocked. When confronted with their mascot’s problematic nature, school trustees, illumni, and fans all echoed the same point, the same point that every supporter of Indigenous mascots makes: “We’re honoring them (Natives).” The concept of honor is always brought up, with honor connoting respect, admire, and worship. Why would your mascot be worshiping a real group of people? It wouldn’t, not if you saw Natives as real people. You worship a god or prophet, not a group of real people. The reason why Native mascots are so normalized is because our society sees Natives as either extinct or a mythical creature. As Peyton Boyd, a Native member of Gen Z said it, “They think that we really aren’t people, in a way. I don’t know how to explain it,” (Nagle). Indigenous people are real and alive today, and the denial of that fact, however vague said denial is, is the erasure of an ethnicity. Even more so, it is the counterfeit romanticization of real people. As Charlene Teters responded to the claim that the fans “love” their chief, “Of course you do, you manufactured him.” Fans see it as a compliment because they like their mascot, but just because a stereotype is seen as positive doesn’t mean it doesn’t cause damage. The warrior stereotype of Indigenous people being strong, aggressive fighters does not help them. It creates a threatening, apathetic, inhumane monolith of Indigenous people. Indigenous people are diverse; There are hundreds of living tribes in the United States, each containing different people with different personalities. Denying such upholds the racist propaganda used in the Native American genocide. Committing a genocide and then using that targeted group to sell t-shirts and tote bags is performative, to say the least. Especially since said mascots were used while the genocide was taking place. If you want to help Native communities, help end systemic alcoholism or poverty on reservations, don’t parade around your puppet of their identity.

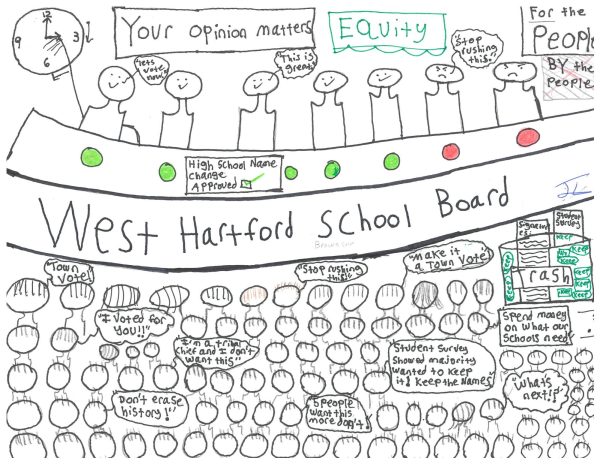

Now, with our West Hartford High School mascots, we don’t have a fake Native running around at halftime, but the damage is still being made. Firstly, the name Chieftain is irreversibly, undeniably a word tied to Indigenous culture. Taking away the offensive caricature doesn’t take away the meaning of the name. It still uses Native Americans as a mascot: An ethnicity is not something one can take off after a game is won. On the West Hartford Public Schools website, under the equity and anti-racism vision, it states, “We make a solemn promise to identify and dismantle all elements of systemic racism and historical inequities.” Anything less than the removal of the Chieftain name would not be following said promise. On the other hand, the term “warrior” has been associated with many different groups. However, when the term was appropriated by Hall High School it was to represent natives, as seen by the old native mascot . Even if the native connotation isn’t obvious, there is still that unerasable history. For instance, at Hall the student-run School spirit squad, Blue Reign, made merchandise with a mini headdress on the Hall ‘H’ (see image to the below).

Even without the mascot, it’s still associated with Indigenous culture, and with this association, is people appropriating said culture. Reassigning a new meaning to something offensive doesn’t change the original meaning, it shows that there is still that connection systemically. Still, we see the effects of anti-Indigenous racism. The name warrior was put into place to represent natives as a mascot. You can’t erase that history. Especially considering they are the remnants of systemic racism and “historical inequities” you claim to care about.

Hall and Conard, even though they don’t still have their previous Native mascots, needed their school team names changed. They promote the discrimination and erasure of Indigenous people. Most of those dismissing it as “not a big deal,” don’t know much about the Native American Genocide other than maybe the Trail of Tears (which is also barely discussed in schools). People deserve to be able to go to school without experiencing dehumanization or denial of their people’s genocide. To uphold the promise of “identify(ing) and dismantle(ing) all elements of systemic racism and historical inequities,” the names had to go.

Works Cited

Brenna, Susan, and Angelina Castagna. “Why are Native Students Being Left Behind? | Teach For America.” Teach for America, https://www.teachforamerica.org/one-day/magazine/why-are-native-students-being-left-behind. Accessed 2 April 2022.

In Whose Honor? Performance by Charlene Teters, PBS, 1997.

“Mascot Definition & Meaning.” Dictionary.com, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/mascot. Accessed 2 April 2022.

“Vision for Equity and Anti-Racism.” West Hartford Public Schools, https://www.whps.org/offices-and-programs/promoting-diversity-staff-advisory-committees/vision-for-equity-and-anti-racism. Accessed 2 April 2022.

Nagle, Rebecca. “Invisibility is the Modern Form of Racism Against Native Americans.” Teen Vogue, 23 October 2018, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/racism-against-native-americans. Accessed 2 April 2022.