West Hartford Community Reflects on Anti-Asian Sentiment

Anti-Asian hate is now on the rise in America, while people and politicians in the US try to combat it.

Anti-Asian Hate in America

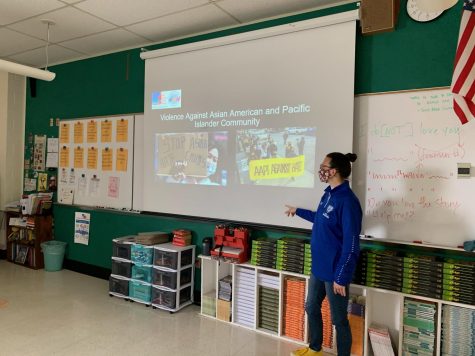

In the midst of a nation-wide movement centered around Asian hate, West Hartford students and staff reflect on the recent anti-Asian violence and speak out about their first-hand experiences of AAPI racism in the local community. This ongoing issue began rising around March of 2020, particularly around the start of Covid-19, and has recently become nationally prevalent. On March 30th, 2021, a 38-year-old man named Brandon Elliot harshly kicked a 65-year-old Asian woman to the ground in New York City. The women sustained multiple injuries, while staff from a store nearby looked on without taking action. Then, on April 15th, 2021, a gunman shot and killed himself along with eight other women of Asian descent, while additionally injuring seven others in Atlanta, Georgia. This rise in anti-Asian hate in the last few months seems to largely be attributed to COVID originating in China.

President Biden said recently, “We can’t be silent in the face of rising violence against Asian Americans.” According to Zignal Labs, a media insights firm, “Since last March, there have been nearly eight million mentions of anti-Asian speech online, much of it falsehoods.” Michael Fu, a high schooler from Atlanta, says, “I think coronavirus has been weaponized in a sense to stigmatize Asian Americans and specifically, Chinese Americans.”

Hall Students Reflect on Racism Against Asians

Alyson Liew, a former Hall High School student, describes her experiences in West Hartford as an Asian American woman. “I never went to [the] administration because I didn’t think they’d do anything, and I also didn’t think it was a big enough issue for anyone to even care about. I did speak to the teachers about it, but they didn’t seem to understand why it was so hurtful to me,” she explains. Liew mentions that many of the racist remarks she encountered were from people taking Chinese classes at Hall. “Peoples’ humor in Chinese class tends to revolve around these few things: All Asians eat dogs. Asian people speak English weirdly. All Asians look the same. Asians are good at math. Asian food smells weird.” Liew also added that the anti-Asian rhetoric in her Chinese class escalated to the point where she went home to her parents crying and begging them to let her quit Chinese. “Nobody would respect me or my culture,” Liew said. “If they could make fun of the way our teacher talked, a person [of] authority, what was stopping them from making fun of my parents? My grandmother?”

Several students at Hall submitted information regarding their experiences with racism against the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) community through a survey. One student anonymously reported that they “have heard people poke fun at the names of AAPI individuals during attendance, particularly when a substitute teacher is in charge of the class.” Another anonymous Hall student reports, “I definitely have seen anti-Asian rhetoric thrown around at Hall but if I’m honest I can’t give specific instances because it’s always the same joke over and over again.”

History of Anti-Asian Sentiment in America

Although violence against the AAPI community has skyrocketed in the past year as a result of hateful rhetoric revolving around the Coronavirus pandemic, the United States is no stranger to racism against the AAPI community. In the mid-1800s, Chinese immigrants began arriving to work on the transcontinental railroad. Chinese resentment gradually began increasing as they began to constitute a larger role in the American workforce. In 1882, the only law that prevented immigration and naturalization based on one’s race in the United States was passed by Congress, known as the Chinese Exclusion Act. This act banned Chinese immigration for 10 years, banned the naturalization of Chinese immigrants, and required Chinese people to obtain certification to re-enter the US if they left. This law greatly decreased the Chinese population in America.

What Americans Need To Do

Emmalee Stewart, an intern counselor at Hall, says that the recent rise in anti-Asian hate can be attributed to “the history of everything that’s gone on . . . with anti-Asian hate and anti-Black hate” because “there’s a precedent for it.” Additionally, Stewart said that “this past year, covid might have had an impact on it whether it’s direct or indirect.” A huge factor that made COVID so influential on people’s perception of Asians, she explained, is the previous president calling it the “Chinese virus,” which created a huge stigma. Shelby West, another intern counselor at Hall, agreed with Stewart in that “the first thing to do is draw awareness to it for everyone…everyone needs to be aware of their preexisting notions and those motives that are driving the stigma…people can be contributing to it and they don’t even know.” She says, “even if people were having these biases and not saying anything about it, this has been an excuse for them to rally in hate.” Stewart and West emphasize that the way to combat this rise in anti-Asian sentiment is for “all ethnicities [to] come together and have a discussion on a national level.” West also says that “I don’t think it’ll be over until someone really stands up for them, someone powerful.”

Alyson Liew concluded, “I just wish my classmates who weren’t Asian could’ve held those people accountable, and explained why their words and actions were harmful. It was clear they would never take me seriously, and I wished so much for one person to say something about how wrong it was. “

“But no one ever did.”